- Joined

- Sep 26, 2021

- Posts

- 6,853

- Main Camera

- Sony

Leonardo noted link between gravity and acceleration centuries before Einstein

Caltech engineers even recreated his experiment with a modern apparatus.

I think he was a space alien.

One key source of confusion is the Ars Technica author describing the primary science paper as saying da Vinci estimated the value of G, the universal gravitational constant. That's the one used in the expression F = G x m_1 x m_2/r^2, where F is the force due to gravity between point masses m_1 and m_2 separated by a distance r. The experiment she describes, by contrast, would instead be one to calculate g, the accleration due to gravity at the surface of the earth. da Vinci could not have estimated G, since at the least it requires Newton's equation for universal gravitation.

In fact, when Gharib et al. used Leonardo's "algorithm" to plot his model and fit that to our modern equations, the measurement for the gravitational constant was 97 percent accurate.

She also says this is da Vinci anticipating Einstein, but that really seems like an overreach, and this is instead da Vinci anticipating Galileo and Newton. That's impressive enough without having to market it by invoking Einstein. And it does a disservice to Galileo, who realized gravity was a force that caused accleration that is independent of mass.

Finally, her description of da Vinci's error in using 2^t instead of t^2 would have been made much clearer if she just supplied the actual equation da Vinci used, with the correct one for comparison. I swear this math aversion these science writers have just leaves people more confused instead of less.

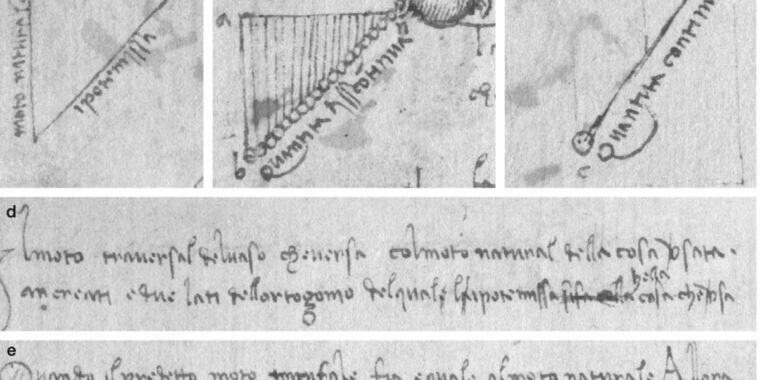

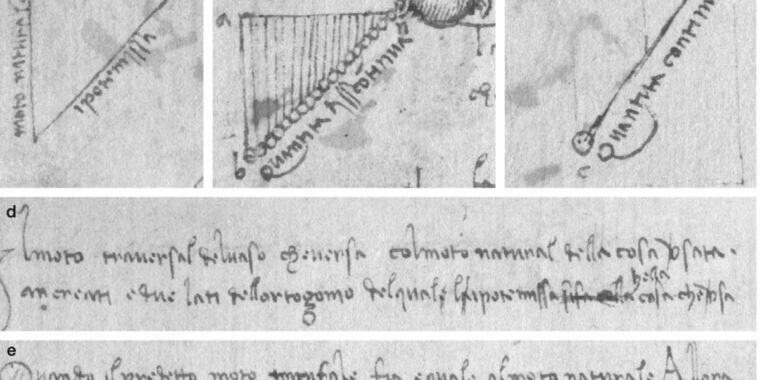

"There was no concept of equations or math, but Leonardo had such an intuitive understanding of math in its non-equation form," Roh told Ars. "I think that's where he started using geometry to write out equations, in a way. Without any tools—no clock—he just uses this geometry as evidence for equalizing the two motions. One [motion] that he can control, one [motion] that he cannot [control] but wants to understand, and the other line to show that they're equalized at every little step. He approached it more like a computer scientist and modeled it more algorithmically."

There’s learning something in a book, but to be one of the first to even conceive of an idea and document it is really something that’s hard to wrap your mind around.

I sometimes wonder how much human knowledge was lost only to be “discovered” again centuries later. Or even concurrent discoveries of principles like electric light that occurred oceans apart but at basically the same time in history, with no interaction between them.

Makes you wonder if there really is “something” out there like Collective Consciousness that we don’t understand.

I was refering to the Ars Technica post, not the article she's referencing (which, unfortunately, I don't have access to):I didn’t read that reference the same way.

Yeah, and this applies not just to ancient thinkers, but to Columbus's contemporaries as well, who are falsely portrayed as not understanding the earth was round, which they certainly did. Where Columbus deviated from the general consensus was instead on its circumference. He did a horrible miscalculation that (along with his overestimation of the width of Asia) led him to conclude Japan (his target) was just 2,700 miles west of the Canary Islands (compared to the actual distance of about 12,000 miles, which was far beyond the capability of any ship at that time). Contemporary scholars knew Columbus's calculations were way off, and that his goal of reaching Japan was impossible, but he nevertheless convinced Luis de Santangel, an important member of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella's court, and the mission was approved (the question of why de Santangel supported this is itself an interesting mystery). Fortunately for Columbus and his crew, he ran into the Bahamas.This happens more frequently than you might think. We also have a habit of distorting our own recording of history which tends to make thinkers of the “ancient world” seem dumber than they were. Aristotle performed experiments that measured the radius of the Earth. Aristarchus pushed the idea of heliocentrism and even speculated that stars were suns, so far away that you couldn’t measure the parallax effect, arguing against geocentric thought from Aristotle, only to have his work lost. But when I was growing up, public education was teaching that Copernicus was the origin of heliocentrism, and people commonly thought the Earth was flat until Columbus “proved” otherwise. I even recall some bits about how this allowed us to move beyond the ancient greek way of thinking of the universe. Despite the fact that apparently they already had a pretty good idea what was up, even if they couldn’t probe it like we can now.

I think he was a space alien.

I was refering to the Ars Technica post, not the article she's referencing (which, unfortunately, I don't have access to):

Where Columbus deviated from the general consensus was instead on its circumference.

Hey, I'm not the only one that saw it that waySo was I. I didn’t read the quoted section the same way you did.

This site uses cookies to help personalise content, tailor your experience and to keep you logged in if you register.

By continuing to use this site, you are consenting to our use of cookies.